Survivor's immunity idol: a case study in rule design

Why do we write so much about Survivor? It inspired The Social Game.

This post contains big spoilers for season 13 of Survivor, and very minor spoilers for seasons 11 and 12.

Determining exactly how and when a game mechanism takes effect matters a lot. And little finicky changes can make massive differences in gameplay. Survivor’s immunity idol is a brilliant case study.

For the uninitiated, here are the absolute basics of Survivor. Contestants live on an island. Every episode, they vote one contestant out at “tribal council.” The last contestant standing wins $1M. One of the longstanding twists in the game is the “immunity idol”: an object hidden in the woods that will keep you safe for one tribal council.

Pretty straightforward concept. But there’s a critical question hidden here: when exactly do you play the idol? Let’s review how tribal council works:

Players discuss the events of the last few days

Players vote

Jeff Probst reads the votes

The player with the most votes goes home

Version 1: Season 11

They first introduced this idea in Season 11. An idol holder could play their idol at tribal council, but before anyone voted. This is plenty powerful: being safe at tribal council is always great. But this version lacks strategic intrigue. Voters have perfect information about the idol. There is no uncertainty or trickery involved. It is powerful, but not terribly interesting.

Version 2: Season 12

In season 12 they made a subtle but massively important adjustment: a player plays their idol after votes are cast, but before votes are read. This is the sweet spot, and it is how idols work today. This mechanism is loaded with strategic potential.

For voters, this means uncertainty about who has an idol, but also who might play an idol. This opens up opportunities to coax and fool voters into voting for someone who plays an idol. The idol player can then negate many votes at once, and orchestrate a “blindside.” This is arguably the hallmark play of modern Survivor.

For the idol holder, we have a different kind of uncertainty. They must play the idol before Jeff Probst reads the votes. This means that they could waste their idol, or not play and go home. This opens up opportunities for voters to outsmart the idol holder, or back them into a corner. “Splitting the vote” (putting half of a bloc’s votes on the presumed idol holder, and half on another player they are allied with) has become common practice. These scenarios add layers of depth to Survivor stratgey, and lead to huge dramatic moments.

The idol’s power scales with its holder’s knowledge and skill. If they know who people are voting for, the idol is immensely powerful: to protect them, and to trick their opponents. If they are ignorant of their tribe’s plans, the idol is worth much less. That is beautiful design. And all from just moving the same exact mechanism one step later in the gameplay loop.

Version 3: Season 13

They tried to take things a step further. The new idol got played after Jeff revealed the votes. Another subtle but massively important shift. This time with some unintended consequences. The player with the idol now bore no risk and faced no uncertainty. Yul found the idol, and realized that he could use it as a cudgel. After all, he faced no uncertainty about when to use it. He could simply hold onto it until he would otherwise be voted out, and use it as a safety net.

Yul was a great player, and this is not meant to take anything away from him. He built a strong alliance, and used his idol to persuade Jonathan to rejoin him, and ultimately won. His opponents knew it would be a waste to vote for him, because he had absolute safety. He was holding a nuclear bomb, and he used it to win the game. But this is substantially less interesting than Version 2. And again, all of this from one subtle change in the sequence of events at Tribal Council.

Fans of the show have dubbed this one time experiment a "super idol." The producers wisely reverted to version 2 after season 13, and that is the idol we are familiar with today. This saga demonstrates how subtle and critical it is to understand how and when things happen in a game. These things matter a lot. and they're hard to predict and understand until you put them into the hands of smart players.

Great gameplay writes its own stories

Good games are story-generating machines. And the most powerful stories in games are not the ones scripted by writers.

I’ve had a lot of great conversations recently with friends about Gabrielle Zevin’s wonderful novel Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow. The book focuses on narrative-driven games, and offers a thoughtful analysis of the relationship between stories and games. This makes sense, because Zevin is a storyteller. But it felt incomplete to me. As I discussed with friends, we talked about games as vehicles for storytelling, and it felt like we were omitting the really profound element of Emergent Narrative, which is what makes games so special.

In their seminal textbook Rules of Play, Katie Salen Tekinbaş and Eric Zimmerman distinguish between two types of narrative in games:

Embedded Narrative: pre-generated narrative content that exists prior to a player’s interaction with the game

Emergent Narrative: unscripted stories that naturally emerge from gameplay

Embedded Narrative

This is Zevin’s concept of games as vehicles for storytelling. Great video games like The Last of Us, The Witcher 3, or Gone Home tell Hollywood stories, and do so with skill and taste. Board games like T.I.M.E. Stories and Gloomhaven incorporate written narrative into gameplay to give players objectives and flavor. Many other games contain lore and backstory that can be largely ignored.

Broadly speaking, games do a poor job of this kind of storytelling. For every The Last of Us, there are dozens of games with half-baked, poorly written stories that fail to enhance and integrate with the gameplay. This is probably because games are made by game designers, not writers. And writing is hard!

But gamers don’t really care about the lack of good embedded stories in games. Why? Because gameplay is king, and will always be more important than Embedded Narrative. If The Witcher 3 had subpar gameplay, we wouldn’t care about how good the story is. Terrible storytelling does not detract from excellent gameplay (see: Neon White, Dark Souls), and neither does the complete absence of storytelling (see: Wingspan, Chess, most board games).

Embedded Narratives are nice to have when they are good, but they are rarely good. And they are unnecessary.

Emergent Narrative

Many media forms can tell stories: prose, poetry, visual art, games, etc. The unique, profound power of games is their ability to generate stories. Emergent Narratives are not scripted by writers – they are a natural consequence of gameplay, and have uncertain outcomes. Great gameplay inevitably causes great stories to exist, because games are interactive, emergent systems.

A few examples:

Basketball has no embedded narrative but creates extraordinary stories (an underdog team hits 10 shots in a row to complete an epic 4th quarter comeback) and meta stories (Lebron returns triumphantly to Cleveland to win a championship and right his wrongs). On Rick and Morty, Rick says that sports are “the opposite of story” and he really couldn’t be more wrong. Look no further than the multi-billion dollar industry of sports journalism, or ESPN’s phenomenal 30 for 30 series for evidence.

The first day I played Elden Ring, I stumbled into an innocuous trap that transported me to a dangerous, far away corner of the game’s enormous map. Confused and bewildered, ill equipped for this level of danger, I slowly struggled through terrifying enemies and a dozen deaths to finally escape the cave I was in, and exit into new territory. That story – a story with no script, a story driven by my own choices and experience, and a story that most other players didn’t even experience for themselves – was infinitely more memorable and meaningful than any of the Embedded Narrative in Elden Ring.

We intentionally chose to put no Embedded Narrative into our game The Social Game. However, my friend group can’t stop telling Pecking Order stories: stories of betrayal, mischief, intrigue, lies, trickery, comebacks, petty vengeance, hilarious spectacle, etc. It actually got to a point where we needed to put a moratorium on telling Pecking Order stories at parties, because people who hadn’t played were getting annoyed. It’s difficult to imagine having written a story so good for this game that our friends would be talking about it years later. But the stories we’ve created through gameplay have left an undeniable mark on all of us.

Good games are story-generating machines. And the most powerful stories in games are not the ones scripted by writers.

Be like Mitch

In 2016, my friend Mitch Prentis visited me while I lived in Indonesia. I had just started to pursue game design. I was fumbling through an explanation of a not-even-half-baked concept for my first game idea. Mitch humored me, listened carefully, and asked good questions for a few hours.

I was explaining the idea so poorly that he misunderstood me and asked, “Wait, are you saying that players prepare cards in 3 different lanes and have to make contingency plans because they don’t know which hand will resolve next? That does sound interesting.” That was not my idea. But I immediately realized that his interpretation was much more interesting than what I had in mind.

I revisited this concept for years, not sure how to make it work. And eventually it became Rampage. I’m not sure what to make of this anecdote. But a few thoughts come to mind.

1. It is worth talking about your ideas, even if you have no clue what you’re doing yet.

2. Good ideas truly come from everywhere — even from a misunderstanding.

3. Having friends like Mitch is invaluable. Strive to be like Mitch.

Why we are focusing on web games

Pecking Order is such a unique experience that people began inviting their friends to test it, their friends invited more friends, and our test server grew organically in ways we never expected. We realized that ultimately the game would need to evolve into a website. Fortunately, many of us already work in software, and we have the skills to build it. We gradually realized that we were in a unique position to build something that felt genuinely new.

When we started designing games in 2018, I set a goal to create 5 functional prototypes in different genres before deciding which prototype to finish and release. I’m interested in all sorts of games, and it was important to explore different genres and mediums to figure out where we could really thrive.

Over the next few years, we made:

Elephant in the Room: a quick abstract strategy game that works as a physical board game or a digital game

Beast Master: a board game with some unique mechanisms

Contingency Plan: a fast paced strategic card battle

The Social Game: a social game played via Discord and the browser

A bunch of other prototypes that are too rotten to show to the public

We built Pecking Order during Covid lockdown because we wanted a game to play via chat in Discord where we were already hanging out. We wanted to play a deep game remotely and asynchronously, because our schedules didn’t always line up. The whole experience of designing and playing this game felt fresh and unique. We wanted to build a social game because social games are amazing, and fit the chat medium really well. This was not a physical game adapted to be played digitally — it was a game tailor made for the experience of chatting with your friends online throughout the day.

There’s a question that people often ask in startups, “What is the thing that you can do better than anyone else?” Michael Porter codified some brilliant ideas about business strategy that are applicable to the design process. Many of his ideas boil down to his thesis “Strategy is about being different.” Products that are easily comparable to competitors end up only differentiating on price, and have a very hard time standing out. Businesses that have products that are truly distinct tend to stand out and grow.

Pecking Order is such a unique experience that people began inviting their friends to test it. Then their friends invited more friends, and our test server grew organically in ways we never expected. We realized that ultimately the game would need to evolve into a website so people could play it outside our Discord server. Fortunately, many of us already work in software, and we have the skills to build it. We gradually realized that we were in a unique position to build something that felt genuinely new.

It turns out that being different is not just good strategy — it’s also more interesting to work on. The problems we’re working on feel novel and unique:

When we run into game design problems, the analogs are less obvious, and so we must think creatively. When I work on Contingency Plan, it’s easy to run into a problem and ask, “How do the 10,000 other card games solve this problem?” But there are far fewer games to compare Pecking Order to, and so creative, lateral thinking is required.

Asynchronous gameplay comes with some weird, unexpected complexity that I outlined in this other blog post. Designing around those problems has actually made the game better.

The mediums of a web app and 24/7 chat open up new, interesting opportunities for gameplay and design. There are all sorts of cool things we can do that aren’t possible in board games.

We are over halfway done with development of the Pecking Order web version. Several members of the team are learning to write code. And now we are cooking up ideas for more web-based social games. There’s some gold in these hills, and we’re determined to find more of it.

We turned the weakest part of Pecking Order into the best part

Pecking Order is a social deduction game, so we are developing it in a highly collaborative way. I had some core ideas nailed down, but was struggling to realize those ideas in a prototype. I brought in a group of friends who are a mix of experienced designers/testers, and game fans who have zero design experience.

The Social Game is a social deduction game, so we are developing it in a highly collaborative way. I had some core ideas nailed down, but was struggling to realize those ideas in a prototype. I brought in a group of friends who are a mix of experienced designers/testers, and game fans who have zero design experience.

Here’s how it works:

Nearly all of the designers of Pecking Order play in every test game, so we are all effectively super-testers of the game. And we play constantly.

The game will eventually be managed by a Bot. But until we build the bot, the game is managed by one of us. The bot is effectively a dungeon master for the game. We intentionally give the person in this role leeway to design their own challenges, make judgment calls when there’s ambiguity about rules, come up with a theme, and to run the game as they see fit (within the parameters of the rules we agreed on beforehand).

At the end of each game, we have a comprehensive retrospective where we review how things went, what new rules we were testing, and what changes we want to make next. We invite everyone to this retro. Pretty much all design decisions are made by majority consensus, and I can say with some honesty that’s it’s been a pretty consistently ego-less, creative discussion every time.

By playing the game a lot and taking turns serving as the bot, we have learned a ton, really fast. Each bot has brought their own flavor to the game, and has introduced new ideas. This structure has also helped us to embrace the best ideas, because every single one of us has had great ideas and horrible ideas — and the merits of each idea are pretty obvious when you’re testing and reviewing as a group. Here’s a case study of how this structure very quickly turned a weak idea into a great idea.

The game mechanism: Pecking Order takes a week to play, and we wanted to have a daily Challenge so that players have short term daily goals and ways to get ahead outside of the big picture victory condition at the end of the week. Winning the Challenge gives you a token, which can be used to buy yourself advantages later in the game.

Version 0: At a random time of day, the bot will post some random Sudoku or Crossword puzzle, and the first player to respond with a correct answer wins a token.

Version 0 bot observation: there is a lot of information in the game that could be used to quiz players such as, “who has the most tokens right now?” It’s much more interesting to make the challenge questions integrate with what’s going on in the game, and to reward players for paying close attention to gameplay.

Version 1: At a random time of day, the bot will post a question about the current state of the game, and the first player to respond with a correct answer wins a token.

Version 1 player observation: there are very few tokens in the game, but tokens and advantages are the most fun part of the game. We wish there were significantly more tokens in play.

Version 1 bot observation: A lot of players are submitting correct answers after another player already won the challenge. This creates a ton of urgency and then bad feelings for players who had the correct answer, but 2 minutes late.

Version 2: At a random time of day, the bot will post a question about the current state of the game, and all players who respond with a correct answer win a token.

Version 2 player observation: this “at a random time of day” structure creates a ton of stress and frustration. Players with kids or demanding jobs or weird life schedules are at an automatic disadvantage on all Challenges. It would be better to leave the challenge open all day, and let players answer on their own time.

Side note: this crucial realization led us to do an overhaul of a whole bunch of other rules to make it so that players never have the experience of urgently needing to take action at any unexpected time of day. Ironically, this improvement is a complete reversal of the original design of the daily challenges.

Version 3: At the beginning of each round, the bot will post a question about the current state of the game, and all players who respond with a correct answer any time this round win a token.

Bot observation: asking questions about the future state of the game would be significantly more interesting than asking questions about the current state of the game. For example, a challenge might say, “who will be in first place tomorrow?” Now players are empowered to affect the future and manipulate the challenge answer by coordinating others to upvote one player and downvote another. Suddenly, a much more interesting layer of strategy emerges for how you will vote, how you talk to your alliances, and how you approach the Challenge. Now challenges reward your amount of knowledge and your ability to control outcomes round to round.

Version 4: At the beginning of each round, the bot will post a question about the future state of the game, and all players who respond with a correct answer any time this round win a token.

Challenges started as arbitrary puzzles that were disconnected from gameplay, and frustrating to players who were not able to check their phones throughout the day. Challenges ended up as questions that drive the core gameplay of voting, and reward players with the best deduction skills and the best ability to coordinate with others to control outcomes round to round. Now, Challenges are probably the most universally beloved part of Pecking Order.

We were able to efficiently diagnose problems and develop this mechanism because we were all super-testers, and all had a chance to manage the game and observe player behavior as the bot. I’ll probably write up some more examples of how this kind of collaborative design helped us move fast and embrace the best ideas in the future. Hyper-collaborative, consensus-driven design is probably not the right path for most projects, but it has worked wonders for Pecking Order.

How to watch Survivor (without spoilers)

As we’ve said before, Survivor is the best game show of all time. But it is also 40 seasons long. So where do you start? Which seasons are best? Do you need to watch it in order? This guide is a systematic way to get you started with Survivor, help you avoid the bad seasons, and make sure that you don’t get spoiled on the best seasons by watching in the wrong order.

Why is this reality TV guide on a game development blog? It inspired The Social Game. You should should play it for yourself!

As we’ve said before, Survivor is the best game show of all time. But it is also has a ridiculous number of seasons. So where do you start? Which seasons are best? Do you need to watch it in order? This guide is a systematic way to get you started with Survivor, help you avoid the bad seasons, and make sure that you don’t get spoiled on the best seasons by watching in the wrong order.

Definitions

Types of seasons:

Standalone: A season with all new cast members.

Reunion: A season with returning contestants from previous seasons. Each of these seasons has prerequisite seasons that introduce the contestants from the reunion season. These seasons are significantly better if you understand the context of the key players, so you should consider seeing the prerequisites before watching the reunions.

Tiers:

T1: Must see TV. Your Survivor experience is categorically incomplete if you miss it.

T2: Highly recommended, but not essential if you only want to watch 5-10 seasons.

T3: Adequate. If you’re a Survivor fan, there’s plenty to enjoy, but it’s not great.

T4: The only people who should watch this are Survivor Completionists.

How to use this guide

If you are unsure about watching Survivor at all, whet your appetite with either Season 7 (very old school, standard definition) or 37 (very new school, high definition) as a litmus test. They are both delightful, and won’t spoil you on anything. If you try one of those and don’t enjoy it, just jump ship immediately — Survivor is not for you.

Begin watching T1 standalone seasons in chronological order (7, 13, and so on). You can jump around between standalone seasons, but in general the show is most enjoyable in chronological order.

If you like what you see, and want to watch more than 5-10 seasons, go back to the beginning and check out some of the T2 seasons. If you LOVE what you see, watch some T3 or T4 seasons. But maintain chronological order if you can stomach the SD early seasons. If you become bored, just skip forward to the next T1 season.

Treat each Reunion season as a stopping point when you should consider whether or not you want to watch some of the lower tier prerequisite seasons. If you’ve seen all the T1 prerequisites, you might want to proceed and see the reunion. If you’re hungry for more, watch some of the T2 or T3 prerequisites before proceeding.

Where to watch

The only place to watch all of Survivor is on Paramount+. There are many seasons on Amazon Prime Video and Hulu as well.

Season Guide

This list is in order (the number on the left is the season number). T1 seasons are bold. Reunion seasons are in italics.

Borneo: T2

Australia: T2

Africa: T4

Marquesas: T3

Thailand: T4

Amazon: T3

Pearl Islands: T1

All Stars: T3

T1 prerequisites: 7. Pearl Islands

T2 prerequisites: 1. Borneo

T3 prerequisites: 2. Australia, 4. Marquesas, 6. Amazon

T4 prerequisites: 3. Africa, 5. Thailand

Vanuatu: T4

Palau: T3

Guatemala: T3

Panama: T3

Cook Islands: T1

Fiji: T3

China: T1

Fans vs. Favorites: T1

T1 prerequisites: 7. Pearl Islands, 13. Cook Islands, 15. China

T3 prerequisites: 12. Panama, 14. Fiji

T4 prerequisites: 9. Vanuatu

Gabon: T3

Tocantins: T2

Samoa: T3

Heroes vs. Villains: T1

T1 prerequisites: 7. Pearl Islands, 13. Cook Islands, 15. China, 16. Fans vs. Favorites

T2 prerequisites: 18. Tocantins

T3 prerequisites: 2. Australia, 4. Marquesas, 8. All-Stars, 10. Palau, 11. Guatemala, 12. Panama, 17. Gabon, 19. Samoa

Nicaragua: T4

Redemption Island: T3

T1 prerequisites: 20. Heroes vs. Villains

T3 prerequisites: 4. Marquesas, 8. All-Stars, 19. Samoa

South Pacific: T4

One World: T4

Philippines: T2

T1 prerequisites: 13. Cook Islands, 16. Fans vs. Favorites

T3 prerequisites: 2. Australia, 19. Samoa

Caramoan: T3

T1 prerequisites: 16. Fans vs. Favorites

T2 prerequisites: 25. Philippines

T3 prerequisites: 17. Gabon, 22. Redemption Island

T4 prerequisites: 21. Nicaragua, 23. South Pacific

Blood vs. Water: T1

T1 prerequisites: 7. Pearl Islands, 13. Cook Islands, 20. Heroes vs. Villains

T2 prerequisites: 1. Borneo, 18. Tocantins

T3 prerequisites: 2. Australia, 8. All-Stars, 12. Panama, 19. Samoa

T4 prerequisites: 24. One World

Cagayan: T1

Blood vs. Water 2: T2

Worlds Apart: T4

Cambodia Second Chance: T1

T1 prerequisites: 7. Pearl Islands, 15. China, 27. Blood vs. Water, 28. Cagayan

T2 prerequisites: 1. Borneo, 18. Tocantins, 25. Philippines, 29. Blood vs. Water 2

T3 prerequisites: 2. Australia, 12. Panama, 19. Samoa

T4 prerequisites: 30. Worlds Apart

Kaoh Rong: T2

Millennials vs. Gen X: T1

Game Changers: T2

T1 prerequisites: 7. Pearl Islands, 13. Cook Islands, 16. Fans vs. Favorites, 20. Heroes vs. Villains, 27. Blood vs. Water, 28. Cagayan, 31. Second Chance, 33. Millennials vs. Gen X

T2 prerequisites: 18. Tocantins, 25. Philippines, 32. Kaoh Rong

T3 prerequisites: 2. Australia, 12. Panama, 22. Redemption Island, 26. Caramoan,

T4 prerequisites: 23. South Pacific, 24. One World, 30. Worlds Apart

Heroes vs. Healers vs. Hustlers: T3

Ghost Island: T3

David vs. Goliath: T1

Edge of Extinction: T3

T1 prerequisites: 31. Second Chance, 33. Millennials vs. Gen X

T2 prerequisites: 29. Blood vs. Water 2, 32. Kaoh Rong, 34. Game Changers

T4 prerequisites: 30. Worlds Apart

Island of the Idols: T4

Winners at War: T1

T1 prerequisites: 7. Pearl Islands, 13. Cook Islands, 16. Fans vs. Favorites, 20. Heroes vs. Villains, 27. Blood vs. Water, 28. Cagayan, 31. Second Chance, 33. Millennials vs. Gen X

T2 prerequisites: 18. Tocantins, 25. Philippines, 29. Blood vs. Water 2, 32. Kaoh Rong, 34. Game Changers, 37. David vs. Goliath

T3 prerequisites: 2. Australia, 4. Marquesas, 8. All-Stars, 11. Guatemala, 22. Redemption Island, 35. Heroes vs. Hustlers vs. Healers, 36. Ghost Island

T4 prerequisites: 3. Africa, 23. South Pacific, 24. One World

Survivor 41: T2

Survivor 42: T3

Survivor 43: T4

Survivor 44: T2

Survivor 45: T2

Survivor 46: T4

Survivor 47: T1

Survivor 48: T3

How we start projects: Spine and Constraints

We have spent 3+ years developing our first board game Beast Master. Part of the reason it has taken so long is that we fumbled around in the dark for the first couple years designing without any constraints or any particular goal in mind. A cool, divergent idea would come up and we had no grounds to say, “no, that’s too far fetched,” or, “that’s simply not what we’re aiming for here.” We ended up accidentally re-designing it into a completely different game more than once. We eventually landed on a game that both of us are proud of, but we spent lots of unnecessary time banging our heads against the wall.

Since then, we’ve started explicitly writing up two things that shape the development of our games: Spine and Constraints. These crucially important concepts provide a huge amount of clarity and focus for us, and give shape projects before we even start prototyping them.

We have spent 3+ years developing our first board game Beast Master. Part of the reason it has taken so long is that we fumbled around in the dark for the first couple years designing without any constraints or any particular goal in mind. A cool, divergent idea would come up and we had no grounds to say, “no, that’s too far fetched,” or, “that’s simply not what we’re aiming for here.” We ended up accidentally re-designing it into a completely different game more than once. We eventually landed on a game that both of us are proud of, but we spent lots of unnecessary time banging our heads against the wall.

Since then, we’ve started explicitly writing up two things that shape the development of our games: Spine and Constraints. These crucially important concepts provide a huge amount of clarity and focus for us, and give shape to our projects before we even start prototyping them.

Spine

Twyla Tharp is a choreographer who has been creating and directing wildly successful dance productions for decades. I know little to nothing about the art of dance, but I know that she wrote a brilliant little book called The Creative Habit. It is chock full of practical ideas for how to lead a creative life and how to do creative work.

One of her stickiest ideas is that a great creative work needs to have a spine that holds it up. She describes a Spine as “private guidance” that can drive the theme and structure of the entire work. “The spine is the statement you make to yourself outlining your intentions for the work... The audience may infer it or not, but if you stick to your spine the piece will work.” The spine is pre-eminent, and it informs every single creative decision you make. You can create something without a Spine, but it will very likely lack coherence, conviction, and confidence.

Constraints

At GDC in 2019 Matthew Davis detailed how he and his team designed the game Into the Breach. I aspire to one day make something as deeply elegant, fresh, thoroughly explored as Into the Breach.

Their development was driven by the constraints that they put on themselves. Davis describes a “hierarchy of constraints” that they implemented as they developed the game. Their design process is a process of narrowing their own options. They’d lock one constraining idea into place (such as: players have perfect information about what the enemies will do next), then survey what was still possible in the game, and implement further constraints from there. They continued narrowing down the mechanisms in the game until the game was an immaculate, clear, and perfect piece of game design. This is similar to the concept we love of “soft vs. steel.” Once we find something that feels great, we throw out other soft ideas that fail to serve the ideas that are working. Once you have a few steely things working together, it becomes obvious what you need to cut, and the game almost begins to design itself.

Certainly there is a time for broad and unconstrained brainstorming. When I’m deciding what kind of project to take on next, it is worthwhile to be extremely open-minded and uncritically explore new and wildly divergent ideas. But once I’ve decided on a project that has a spine, it’s crucial that I set up some basic guardrails for myself to focus my creative thinking onto how to make the most of the confined little idea that I’m trying to develop. Without guardrails to guide brainstorms, the space of possibilities is simply too large to be manageable. This kind of focus makes mere concepts blossom into fully realized games.

Here’s a glance at what this looks like with the two most recent games we’re working on.

Rampage

Spine: you must build hands and manage your deck to win battles in a way that also prepares you for all contingencies, and preserves your best cards for future battles.

Constraints: less than 5 minutes to learn, both players have identical decks, the entire game consists of 54-108 cards, and game play must have enough variance to be extremely re-playable without adding more cards.

With Spine and Constraints in place, I was able to rapidly generate dozens of ideas for cards. Some worked and some didn’t. Some were interesting, but felt misaligned from the Spine I wanted. I was suddenly free to confidently shelve cool ideas and say, “no” because I had guardrails. I was able to really deeply explore this little idea of building multiple contingent hands, and the result is a focused and fun game that represents the best game design I’ve ever done.

Pecking Order

The Spine and Constraints of Pecking Order were borne of necessity. When Covid-19 hit, we were suddenly not able to test games in person, but we wanted to make a cut-throat social game that we could play together remotely.

Spine: All game play, sharing of asymmetric information, deduction, cooperation, and betrayal is handled through text communication, and players can communicate as much or as little as they want.

Constraints: less than 3 minutes to learn the rules, includes no components other than Discord or Slack, players don’t get eliminated, and game play should vary majorly depending on who is playing and how experienced the players are.

Designing a game with no components and few rules was extremely restricting. It forced us to think very differently about design and throw out loads of cool ideas that are simply too complex for this medium. What we were left with was a hyper-focused, and truly addictive game we can’t stop playing.

How we make beautiful cards fast with Figma + Google Sheets

We’ve been trying out different ways to prototype cards for years, and I wanted to quickly share the best thing we’ve found. When we prototype and test, we need to create and print components in a way that is:

Fast

Cheap

Presentable (if not beautiful)

Easy to update

There are obvious tradeoffs between these four requirements. Scribbling on note cards is fast and cheap, but it looks terrible and updating cards is tedious and time-consuming. Printing text on printer paper and taping it to old business cards looks slightly better, but it’s still amateurish and takes too long to update. The key to a great process is that we need to be able to make small changes to existing cards, and create wholly new cards very rapidly without sacrificing presentation or spending a lot of money.

We’ve been trying out different ways to prototype cards for years, and I wanted to quickly share the best thing we’ve found. When we prototype and test, we need to create and print components in a way that is:

Fast

Cheap

Presentable (if not beautiful)

Easy to update

Sample cards from Contingency Plan

There are obvious tradeoffs between these four requirements. Scribbling on note cards is fast and cheap, but it looks terrible and updating cards is tedious and time-consuming. Printing text on printer paper and taping it to old business cards looks slightly better, but it’s still amateurish and takes too long to update. The key to a great process is that we need to be able to make small changes to existing cards, and create wholly new cards very rapidly without sacrificing presentation or spending a lot of money.

The process in the video below is the best thing we’ve found for the following reasons:

Fast: Figma is extremely user-friendly and easy to use.

Cheap: This whole process uses free tools. Printing on cardstock can be pricey, but you can trim down costs by not using color, and using cheaper paper.

Presentable: Figma makes it easy to make beautiful cards at scale. You don’t have to be a designer to make things look good there. Walter (Product Desginer at DropBox) and I (Product Manager at Binti) use it constantly for work. It works for designing software, it works for designing card games. It’s an amazing tool.

Easy to update: The workflow with Google Sheets allows me to update the entire deck and create a new print file in seconds.

Here’s how it works:

You can see the detailed process in the video above, but the key steps are:

Put all of your card information into a Google Sheet. Use the first row to name the different text fields on the cards (such as Title, Body, and Power). Make sure that your sharing settings on the sheet are set to “Anyone on the internet with this link can view.”

Install Google Sheets Sync on your Figma account.

Design a card in Figma, and name the different text fields using a # for the name of the column you want to reference in your Google Sheet.

Create a Component by right-clicking on the card and selecting “Create Component”

Create a Frame, and name it “// “ followed by the name of the tab in your Google Sheet

Click on “Assets” in the top left of Figma, and drag and drop copies of your card component into your Frame.

Right click on the frame, click Plug-ins, and run the Google Sheets Sync. Paste the link to your Google Sheet, and run.

You can either download using “Export” in the bottom right of Figma. Depending what you want to do with the cards, you could either download individual cards and upload to something like Tabletop Simulator, or put them onto a 8 1/2” x 11” PDF to send to print on cardstock.

Why we are making a social game

During the pandemic, it has been hard to test board games, so we started developing Pecking Order: a cut throat social game you play in Discord or Slack over the course of a week. This idea has been simmering for years as I fell deeply in love with two social games: Survivor and Codenames.

These are two very different games that both beautifully illustrate something we want to emulate: communication is the core gameplay, and there’s tremendous freedom in how players communicate. Communication is improvisational, relational, idiosyncratic, and creative. Communication can be radically different depending on the participants and the context. Communication as a game mechanism brings pre-existing human factors to the game, and offers a massive space of possibility for players to devise strategies and styles. And as a result, good social games reward creativity, and vary massively depending on who is playing.

During the pandemic, it has been hard to test board games, so we started developing Pecking Order: a cut throat social game you play in Discord or Slack over the course of a week. This idea has been simmering for years as I fell deeply in love with two social games: Survivor and Codenames.

These are two very different games that both beautifully illustrate something we want to emulate: communication is the core gameplay, and there’s tremendous freedom in how players communicate. Communication is improvisational, relational, idiosyncratic, and creative. Communication can be radically different depending on the participants and the context. Communication as a game mechanism brings pre-existing human factors to the game, and offers a massive space of possibility for players to devise strategies and styles. And as a result, good social games reward creativity, and vary massively depending on who is playing.

Survivor

Survivor is a brilliant social game masquerading as Reality TV. Survivor just might be the best game show of all time (tied with Jeopardy, the perfect quiz show). I have so much to say about Survivor, and am working on a Survivor Redux guide for people who want to experience the very best of its 40 seasons without slogging through all of them. But for today, let’s just focus on one aspect of Survivor that inspired us.

Survivor has simple rules, and extreme variability in gameplay because it is a pure social game. The rules of the game are straightforward:

Don’t get voted out by your tribemates.

Compete in puzzles and obstacle courses to get immunity from votes.

Remain likable enough to impress a jury of losers to win the game.

Lurking behind those simple objectives is communication. Players have to persuade, cajole, coordinate with, and even trust their opponents to get anything done, and ultimately to win. It makes for excellent television because the victory condition is so brutally simple that it forces your attention onto the social acrobatics, genuine relationships, and tedious lying that people will do to persuade the group to not send them home.

Survivor is a fundamentally different game depending on who is playing. It’s a different game when there are returning contestants whose strategy from previous seasons is well known to the other contestants. It’s a different game when all the players have studied 30+ seasons’ worth of strategy before competing themselves. It’s a different game when players compete against their family members. It’s a different game when the final jury appreciates clever deception more than loyalty.

The immense variability of Survivor’s gameplay and its deep, robust, ever-evolving strategy is a credit to its simple rules and its focus on communication.

Codenames

Codenames is a word game that depends on strategic communication. It is not a pure social game like Surivor, but it illustrates the same concept.

The main gameplay loop is deceptively difficult. The clue-giver must see some conceptual relationship between two or more of the words on the table (while avoiding other words), then communicate that relationship to the guessers with a one-word clue. It's a damn brainteaser to come up with a good clue that triggers your teammates to recognize the conceptual relationship so they can choose the right words. Simple rules, and an extremely large space of possible clues reward players for creative communication.

The social component of Codenames is not an afterthought. The victory condition actually depends on this brilliant and challenging bit of improvised communication. Gameplay is quite different depending on who is playing. You might give very different clues while playing with strangers at the game store vs. playing with your closest friends and family members, with whom you can draw on shared experiences and inside jokes. In a real sense, you're playing with different stuff in these two scenarios.

Pecking Order

Our goal is to build a game with simple rules and varied gameplay. We want to make a pure social game that can be played 1,000 different ways, and rewards creativity. We want to make a game that depends on communication, and evolves when the same group of people play it over and over.

We’re currently testing the game in our Discord Server and we’re really loving it. You’re welcome to join for a future round if you’d like to give it a try!

Our game design syntax

In the first half of 2018, we went from index card cutouts to a fully fledged v1 of Odra (a working title that we quickly dismissed as wannabe sci-fi). We knew that there were problems with the game, but we lacked a systematic way to diagnose those problems. One big issue we ran into was that we were fine tuning every part of the game simultaneously. Games are finicky systems. Each part of it is hydraulically linked to all the other parts of it. Small adjustments to the rules can result in huge changes in player experience. On a few occasions we changed 3 or 4 little things at once and managed to completely break the game.

This blog post is about the syntax we used to audit our game systematically, evaluate each part of the game independently, identify what needed work, and ultimately allow us to rebuild the game around its best parts.

In the first half of 2018, we went from index card cutouts to a fully fledged v1 of Odra (a working title that we quickly dismissed as wannabe sci-fi). We knew that there were problems with the game, but we lacked a systematic way to diagnose those problems. One big issue we ran into was that we were fine tuning every part of the game simultaneously. Games are finicky systems. Each part of it is hydraulically linked to all the other parts of it. Small adjustments to the rules can result in huge changes in player experience. On a few occasions we changed 3 or 4 little things at once and managed to completely break the game.

This blog post is about the syntax we used to audit our game systematically, evaluate each part of the game independently, identify what needed work, and ultimately allow us to rebuild the game around its best parts.

Rule vs Component vs Loop

First, we triaged each part of the game into 3 broad categories: rules, components, and gameplay loops. Rules are rules, and there are rules that apply to just about everything. Components are the stuff that players interact with to play the game. Loops are sets of activities that players perform repeatedly in pursuit of victory.

Core vs Ancillary

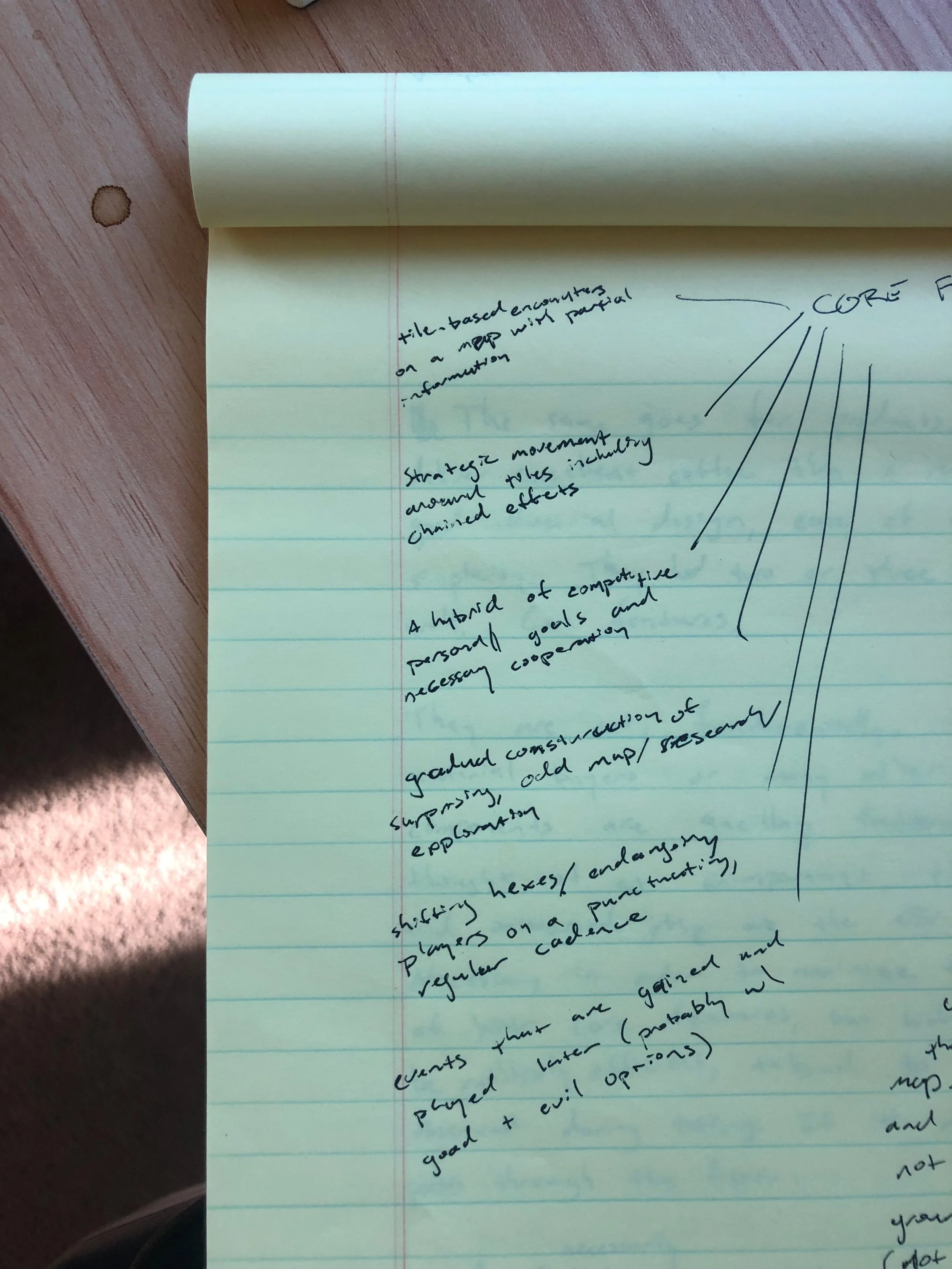

By testing over and over and over, we discovered a small handful of ideas that hung together particularly well, and were a consistent source of fun. Specifically, we fell in love with:

Attempting to define the “Core” parts of the player experience

Exploration of a dynamic map of hexagonal tiles with hidden information

Interesting movement between each hexagon that includes chained, cascading effects

Big, exciting events that you can play at any time, and affect everyone

Some sort of punctuating, repeating attack from an automated villain who prowls around the map and kills players between turns

That’s our 30 seconds of fun. That’s the core. All of that stuff is essential to the player experience we’re creating. Sometimes you don’t get to decide whether something is core. The board is what players will be staring at for most of the game. The gameplay loop of a “turn” is the set of activities that players will do over and over for the whole game. Those types of things are core whether we want them to be or not.

But we definitely didn’t care about all the other parts of the game that much as we cared about the core stuff. For example, we had many long discussions about how best to implement the currency system. We tested lots of ideas, and came up with some fun ones. But when we audited the game after testing v1 a lot, the currency itself wasn’t a source of fun. It had an important role to play — currency governed how much a player could do on a given turn, and presented an interesting trade system. But it wasn’t the main show. It served a necessary support role to make the current rule set work, but it was not primary to the player experience. We call these kinds of components and rules ancillary. Our opinion is that ancillary components and rules should be quiet and reliable, and fold seamlessly into the player experience without drawing attention to themselves. Here are the guiding principles for our ancillary components and rules:

Purposeful: It must achieve a goal or solve a problem that nothing else in the game solves. The total number of ancillary elements should be minimized, so elements which address multiple goals / problems simultaneously are preferable.

Minimal: It must be ruthlessly efficient in getting the player to their desired outcome. In the words of John Roderick, ancillary elements should keep players moving and get out of the way.

Integral: It must enhance the experience of performing the core activities of the game and inform the player about who they are and what they are doing. It must be integral to the whole of the game.

It’s not always this straightforwad, but we declared everything in the game to be either ancillary or core. Now we could begin to assess every part of the game in light of how well it served the core player experience. For example, we loved the player experience of exploring tiles while avoiding an automated villain. However, the components and rules we used to implement that in v1 were clunky and confusing. This was no major problem. There are 10,000 ways to pose danger to players and shift tiles randomly. The components and rules that will evoke that player experience are ancillary, and therefore replaceable.

Steel vs Soft

Finally, we categorized everything according to the old adage, “If you meet steel, then stop. If you meet mush, then push.” We found that it was really important to put our pencils down on things that felt like steel so that we could focus on the stuff that still felt soft.

Putting all the pieces together, we could summarize the whole game using this syntax. The board shape is good, but it might be better with smaller spaces and more spaces: core component (soft). The rules for dealing with currency are a fair way to manage player turns, but they are clunky in practice: ancillary component (soft). Hexagonal Tiles are great as they are: core component (steel). The victory condition is extremely important, but it’s kind of anticlimactic right now: core rule (soft).

v2

Finishing v2

We started locking some pieces into place, and that made subsequent decisions even easier. Each time we locked something in as steel, the scope of possibilities for all the remaining soft components and rules around it would shrink. Using this method to develop a v2, we ended up recreating the game into something quite different once again. In fact, we may have been too liberal with our changes. We ditched all the soft ancillary stuff, and built a fresh game around the core stuff that we loved. Here’s what we changed:

Simplified tiles to just a few different broad categories to make it easier for players to quickly understand what they were looking at.

Shrunk the size of tiles, and added 10 spaces to the board.

Replaced the villain with 4 payloads that could be worth different points, based on player bidding.

Shortened the player’s turn so the gameplay is much faster and simpler. Feels less like a strategy game and more like a sport.

Players now started in different corners of the board instead of moving linearly across the board together.

It was a fairly fun game, but it felt nothing like the v1 that we loved so much. Mildly discouraged, we put v2 on the shelf for a couple months while working on other games. Then in November 2018 we suddenly realized that we could incorporate our learnings from v2 to solve the problems of v1 while preserving that original player experience that we lost in v2. Now we are neck deep developing v3, which combines the best features of the first two versions, and feels significantly better than both of them. But that’s a blog post for another day.

30 Seconds of Fun

Walter and I have been “designing games” in our mind palace for years. We thought up a puzzle-based competitive iOS game, a Jackbox-esque multi-screen heist game, and an epic superhero role-based strategy board game. We talked on Skype and imagined exciting, novel games that had beginnings, middles, and ends. They were sort of like un-playable, puffed up thought experiments. And because they weren’t real yet, they sounded elegant, fair, and perfectly balanced.

We had misplaced confidence in the quality of our ideas, because no player had yet given us that blank stare that says, “this rule makes no sense and there’s a typo on the card… and by the way this isn’t fun.” They needed rigorous editing and brutal feedback and fresh eyes. They needed to be tested.

Walter and I have been “designing games” in our mind palace for years. We thought up a puzzle-based competitive iOS game, a Jackbox-esque multi-screen heist game, and an epic superhero role-based strategy board game. We talked on Skype and imagined exciting, novel games that had beginnings, middles, and ends. They were sort of like un-playable, puffed up thought experiments. And because they weren’t real yet, they sounded elegant, fair, and perfectly balanced.

We had misplaced confidence in the quality of our ideas, because no player had yet given us that blank stare that says, “this rule makes no sense and there’s a typo on the card… and by the way this isn’t fun.” They needed rigorous editing and brutal feedback and fresh eyes. They needed to be tested.

Walter’s floor after our first day. We used lots of components from other games for things like currency and people.

Moving from the mind palace to the real

In January 2018, we decided to change our approach and get serious. And by “get serious,” I mean, “Buy index cards and sharpies.” Our strongest, simplest idea was a game where players bid different amounts of resources to commission space ships and send them on a dangerous journey (the mechanisms for competitively bidding on multiple risky entities mimics venture capital investing, which was my day job). Without any sense of how the game worked, we started cutting little ships and pushing them around Walter’s carpet back and forth between an origin planet and a destination planet. Extremely basic stuff.

At first, we just wanted to stress-test the basic engineering of the game. These crummy index cards exposed some obvious initial questions with much deeper questions behind them:

Obvious questions: how far can ships move from a given location? are there spaces between them?

Looming questions: where are we, what are these locations, why are we motivated to move between them?

Obvious questions: how do players move about the board? do they have turns with limited movement?

Looming questions: who is the player, what are they doing here, what does a turn feel like, and why?

Immediately, the tactile experience of pushing index cards around sharpened the game. By the end of the day, we had basic, fair rules about movement, and it felt good. The game was resolutely un-fun, but we had our first few rules. Then we played it with Walter’s unbelievably patient wife Toria, who exposed a bunch of other blind spots. We made more progress on that Saturday than we had made in the last three years. Since then, we have had a major design sessions or play tests almost every week. We repeated this process for months, the best features of the game percolated to the top, and the half-baked filler ideas started to look weak and bland.

Once we had a game that more or less hung together, we began looking for something much more mysterious: fun.

30 Seconds of Fun

These play tests were in pursuit of some great, repeatable experiences within the constraints of the prototype. By tinkering with the components of the game, interesting little movement mechanics or a satisfying progression cycle or a set of dynamic problems would emerge. We wanted to find the best features, and focus the entire game around them. We needed some activity or decision at the center of the game that you could do 1000 times before getting bored.

We refer to this hook as the “30 seconds of fun.” That’s how Jaime Griesemer described the design process of the player experience in Halo.

“In Halo 1, there was maybe 30 seconds of fun that happened over and over and over again, so if you can get 30 seconds of fun, you can pretty much stretch that out to be an entire game… but if you don’t nail that 30 seconds, you’re not gonna have a great game.”

We didn’t yet know what our 30 seconds are, but we know the fastest way to find it is by playing the game. A lot.

v0.1 consisted of a 25 space board, hexagons with crazy encounters, specialized ships, a currency (fuel for ship movement), and a villain who prowled around the map autonomously between turns.

Finishing v1

Many ideas worked elegantly in the mind palace, but created friction and confusion for players in practice. Physically moving cardboard and plastic on a table and watching the reactions of friends and family forced all of our design decisions to be practical, understandable, and integral with the other components in the game. We mercilessly chopped everything that didn’t work, and the game evolved quickly into something pretty different. We tested this way for months, sharpening the good, purging the bad, and always keeping the game intact and ready to play each week. In July, we landed on v0.1 of the game

We played v1 throughout June and July. Since then, we developed and shelved a v2, refining our design process along the way. And now we are testing v3 at board game shops! Our design process is still based on rapid iterations and ongoing tests, but includes a system for tracking and categorizing all the components and rules. That’s a blog post for another day.