Our game design syntax

In the first half of 2018, we went from index card cutouts to a fully fledged v1 of Odra (a working title that we quickly dismissed as wannabe sci-fi). We knew that there were problems with the game, but we lacked a systematic way to diagnose those problems. One big issue we ran into was that we were fine tuning every part of the game simultaneously. Games are finicky systems. Each part of it is hydraulically linked to all the other parts of it. Small adjustments to the rules can result in huge changes in player experience. On a few occasions we changed 3 or 4 little things at once and managed to completely break the game.

This blog post is about the syntax we used to audit our game systematically, evaluate each part of the game independently, identify what needed work, and ultimately allow us to rebuild the game around its best parts.

In the first half of 2018, we went from index card cutouts to a fully fledged v1 of Odra (a working title that we quickly dismissed as wannabe sci-fi). We knew that there were problems with the game, but we lacked a systematic way to diagnose those problems. One big issue we ran into was that we were fine tuning every part of the game simultaneously. Games are finicky systems. Each part of it is hydraulically linked to all the other parts of it. Small adjustments to the rules can result in huge changes in player experience. On a few occasions we changed 3 or 4 little things at once and managed to completely break the game.

This blog post is about the syntax we used to audit our game systematically, evaluate each part of the game independently, identify what needed work, and ultimately allow us to rebuild the game around its best parts.

Rule vs Component vs Loop

First, we triaged each part of the game into 3 broad categories: rules, components, and gameplay loops. Rules are rules, and there are rules that apply to just about everything. Components are the stuff that players interact with to play the game. Loops are sets of activities that players perform repeatedly in pursuit of victory.

Core vs Ancillary

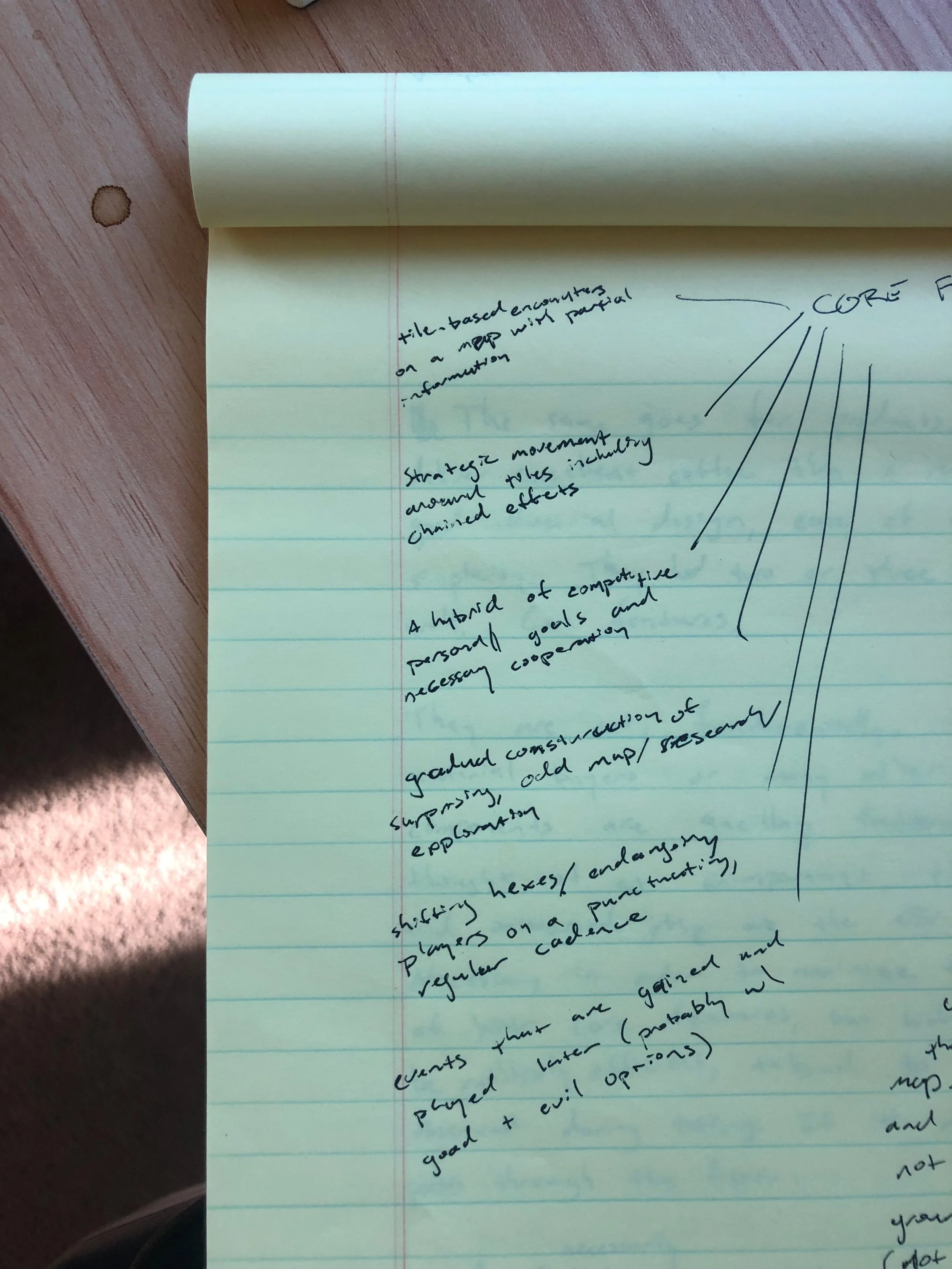

By testing over and over and over, we discovered a small handful of ideas that hung together particularly well, and were a consistent source of fun. Specifically, we fell in love with:

Attempting to define the “Core” parts of the player experience

Exploration of a dynamic map of hexagonal tiles with hidden information

Interesting movement between each hexagon that includes chained, cascading effects

Big, exciting events that you can play at any time, and affect everyone

Some sort of punctuating, repeating attack from an automated villain who prowls around the map and kills players between turns

That’s our 30 seconds of fun. That’s the core. All of that stuff is essential to the player experience we’re creating. Sometimes you don’t get to decide whether something is core. The board is what players will be staring at for most of the game. The gameplay loop of a “turn” is the set of activities that players will do over and over for the whole game. Those types of things are core whether we want them to be or not.

But we definitely didn’t care about all the other parts of the game that much as we cared about the core stuff. For example, we had many long discussions about how best to implement the currency system. We tested lots of ideas, and came up with some fun ones. But when we audited the game after testing v1 a lot, the currency itself wasn’t a source of fun. It had an important role to play — currency governed how much a player could do on a given turn, and presented an interesting trade system. But it wasn’t the main show. It served a necessary support role to make the current rule set work, but it was not primary to the player experience. We call these kinds of components and rules ancillary. Our opinion is that ancillary components and rules should be quiet and reliable, and fold seamlessly into the player experience without drawing attention to themselves. Here are the guiding principles for our ancillary components and rules:

Purposeful: It must achieve a goal or solve a problem that nothing else in the game solves. The total number of ancillary elements should be minimized, so elements which address multiple goals / problems simultaneously are preferable.

Minimal: It must be ruthlessly efficient in getting the player to their desired outcome. In the words of John Roderick, ancillary elements should keep players moving and get out of the way.

Integral: It must enhance the experience of performing the core activities of the game and inform the player about who they are and what they are doing. It must be integral to the whole of the game.

It’s not always this straightforwad, but we declared everything in the game to be either ancillary or core. Now we could begin to assess every part of the game in light of how well it served the core player experience. For example, we loved the player experience of exploring tiles while avoiding an automated villain. However, the components and rules we used to implement that in v1 were clunky and confusing. This was no major problem. There are 10,000 ways to pose danger to players and shift tiles randomly. The components and rules that will evoke that player experience are ancillary, and therefore replaceable.

Steel vs Soft

Finally, we categorized everything according to the old adage, “If you meet steel, then stop. If you meet mush, then push.” We found that it was really important to put our pencils down on things that felt like steel so that we could focus on the stuff that still felt soft.

Putting all the pieces together, we could summarize the whole game using this syntax. The board shape is good, but it might be better with smaller spaces and more spaces: core component (soft). The rules for dealing with currency are a fair way to manage player turns, but they are clunky in practice: ancillary component (soft). Hexagonal Tiles are great as they are: core component (steel). The victory condition is extremely important, but it’s kind of anticlimactic right now: core rule (soft).

v2

Finishing v2

We started locking some pieces into place, and that made subsequent decisions even easier. Each time we locked something in as steel, the scope of possibilities for all the remaining soft components and rules around it would shrink. Using this method to develop a v2, we ended up recreating the game into something quite different once again. In fact, we may have been too liberal with our changes. We ditched all the soft ancillary stuff, and built a fresh game around the core stuff that we loved. Here’s what we changed:

Simplified tiles to just a few different broad categories to make it easier for players to quickly understand what they were looking at.

Shrunk the size of tiles, and added 10 spaces to the board.

Replaced the villain with 4 payloads that could be worth different points, based on player bidding.

Shortened the player’s turn so the gameplay is much faster and simpler. Feels less like a strategy game and more like a sport.

Players now started in different corners of the board instead of moving linearly across the board together.

It was a fairly fun game, but it felt nothing like the v1 that we loved so much. Mildly discouraged, we put v2 on the shelf for a couple months while working on other games. Then in November 2018 we suddenly realized that we could incorporate our learnings from v2 to solve the problems of v1 while preserving that original player experience that we lost in v2. Now we are neck deep developing v3, which combines the best features of the first two versions, and feels significantly better than both of them. But that’s a blog post for another day.

30 Seconds of Fun

Walter and I have been “designing games” in our mind palace for years. We thought up a puzzle-based competitive iOS game, a Jackbox-esque multi-screen heist game, and an epic superhero role-based strategy board game. We talked on Skype and imagined exciting, novel games that had beginnings, middles, and ends. They were sort of like un-playable, puffed up thought experiments. And because they weren’t real yet, they sounded elegant, fair, and perfectly balanced.

We had misplaced confidence in the quality of our ideas, because no player had yet given us that blank stare that says, “this rule makes no sense and there’s a typo on the card… and by the way this isn’t fun.” They needed rigorous editing and brutal feedback and fresh eyes. They needed to be tested.

Walter and I have been “designing games” in our mind palace for years. We thought up a puzzle-based competitive iOS game, a Jackbox-esque multi-screen heist game, and an epic superhero role-based strategy board game. We talked on Skype and imagined exciting, novel games that had beginnings, middles, and ends. They were sort of like un-playable, puffed up thought experiments. And because they weren’t real yet, they sounded elegant, fair, and perfectly balanced.

We had misplaced confidence in the quality of our ideas, because no player had yet given us that blank stare that says, “this rule makes no sense and there’s a typo on the card… and by the way this isn’t fun.” They needed rigorous editing and brutal feedback and fresh eyes. They needed to be tested.

Walter’s floor after our first day. We used lots of components from other games for things like currency and people.

Moving from the mind palace to the real

In January 2018, we decided to change our approach and get serious. And by “get serious,” I mean, “Buy index cards and sharpies.” Our strongest, simplest idea was a game where players bid different amounts of resources to commission space ships and send them on a dangerous journey (the mechanisms for competitively bidding on multiple risky entities mimics venture capital investing, which was my day job). Without any sense of how the game worked, we started cutting little ships and pushing them around Walter’s carpet back and forth between an origin planet and a destination planet. Extremely basic stuff.

At first, we just wanted to stress-test the basic engineering of the game. These crummy index cards exposed some obvious initial questions with much deeper questions behind them:

Obvious questions: how far can ships move from a given location? are there spaces between them?

Looming questions: where are we, what are these locations, why are we motivated to move between them?

Obvious questions: how do players move about the board? do they have turns with limited movement?

Looming questions: who is the player, what are they doing here, what does a turn feel like, and why?

Immediately, the tactile experience of pushing index cards around sharpened the game. By the end of the day, we had basic, fair rules about movement, and it felt good. The game was resolutely un-fun, but we had our first few rules. Then we played it with Walter’s unbelievably patient wife Toria, who exposed a bunch of other blind spots. We made more progress on that Saturday than we had made in the last three years. Since then, we have had a major design sessions or play tests almost every week. We repeated this process for months, the best features of the game percolated to the top, and the half-baked filler ideas started to look weak and bland.

Once we had a game that more or less hung together, we began looking for something much more mysterious: fun.

30 Seconds of Fun

These play tests were in pursuit of some great, repeatable experiences within the constraints of the prototype. By tinkering with the components of the game, interesting little movement mechanics or a satisfying progression cycle or a set of dynamic problems would emerge. We wanted to find the best features, and focus the entire game around them. We needed some activity or decision at the center of the game that you could do 1000 times before getting bored.

We refer to this hook as the “30 seconds of fun.” That’s how Jaime Griesemer described the design process of the player experience in Halo.

“In Halo 1, there was maybe 30 seconds of fun that happened over and over and over again, so if you can get 30 seconds of fun, you can pretty much stretch that out to be an entire game… but if you don’t nail that 30 seconds, you’re not gonna have a great game.”

We didn’t yet know what our 30 seconds are, but we know the fastest way to find it is by playing the game. A lot.

v0.1 consisted of a 25 space board, hexagons with crazy encounters, specialized ships, a currency (fuel for ship movement), and a villain who prowled around the map autonomously between turns.

Finishing v1

Many ideas worked elegantly in the mind palace, but created friction and confusion for players in practice. Physically moving cardboard and plastic on a table and watching the reactions of friends and family forced all of our design decisions to be practical, understandable, and integral with the other components in the game. We mercilessly chopped everything that didn’t work, and the game evolved quickly into something pretty different. We tested this way for months, sharpening the good, purging the bad, and always keeping the game intact and ready to play each week. In July, we landed on v0.1 of the game

We played v1 throughout June and July. Since then, we developed and shelved a v2, refining our design process along the way. And now we are testing v3 at board game shops! Our design process is still based on rapid iterations and ongoing tests, but includes a system for tracking and categorizing all the components and rules. That’s a blog post for another day.